The complexity of the global food debate is staggering. Food is simultaneously global and local, always a necessity and sometimes a luxury, both a contributor to and potential solution for the climate crisis. Faced with this complexity, intergovernmental organisations, think tanks and start-ups have devoted themselves to defining a new food system: one that balances supply with demand and leaves little-to-no environmental damage. Yet the design of these systems is imperative, and it seems that we currently run the risk of replacing one unjust system with another.

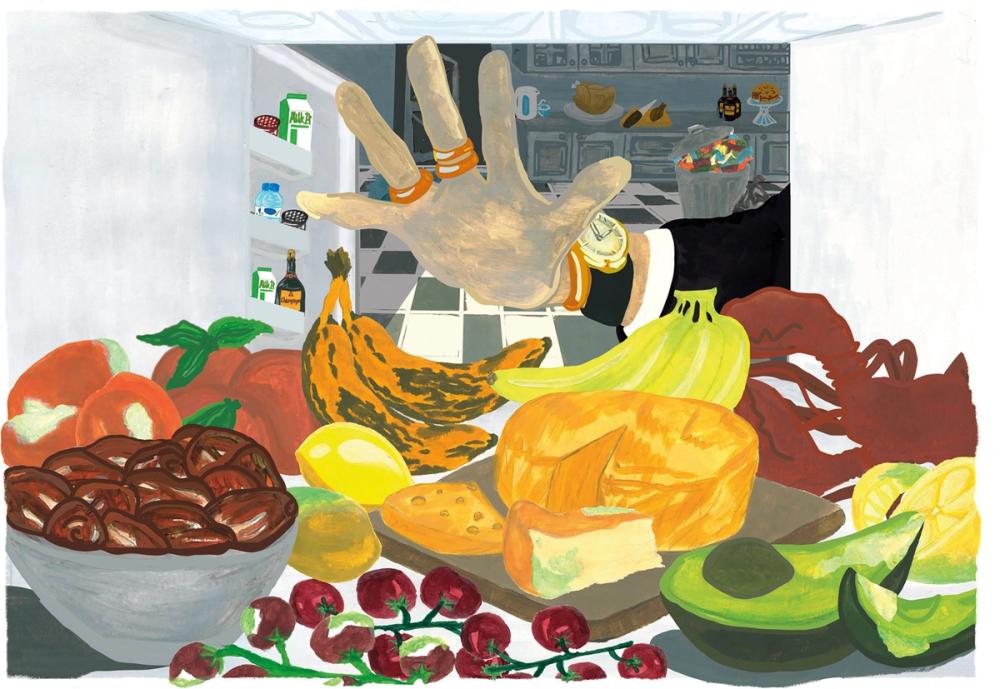

Think back to the last time you chopped vegetables: what did you store away in freezer bags, what did you set aside for your meal that evening, and what did you have left at the end? Food bloggers have been fashioning all manner of creative concoctions from the odds and ends of organic matter: from and broths, to slaw and crisps, to smoothies and curries, the bits of vegetables that nobody wants are suddenly fashionable to consume. As they should be: these otherwise-unloved ends – peels, skins, ‘butts’, leaves, cores, stems, and seeds as well – are full of fibre and antioxidants, and should be consumed with the rest of the vegetable.

The food waste problem is usually centred on just how many households and food shops are discarding pre-packaged, perfectly edible food products. It goes without saying that this, in itself, has a devastating impact on the climate, not only in the form of waste, but also in the amount of energy and water required to grow and harvest these products in the first place. But we must also consider the next level down: the underutilised food, or these odds and ends that get tossed. Tamara Green of The Food Network suggests that we should ‘think of the greens attached to [...] radishes as a two-for-one deal.’ With climate change, the global coronavirus pandemic, and nationalist politics all threatening our food supply chains, she might be onto something. The Zero-Waste and Root-to-Stem Movements are a logical next step in conversations about lifestyle and food waste.

My grandmother, after making chai traditionally in a metal vessel, will quite literally squeeze the teabags to get as much out of each one as she can muster the strength to.

While the reuse of food ends may be an emerging fad among white, middle-class communities, finding flavour in vegetable scraps is something that communities of colour have long championed. Migrant communities with limited resources have always had to squeeze food to its highest potential; my grandmother, after making chai traditionally in a metal vessel, will quite literally squeeze the teabags to get as much out of each one as she can muster the strength to. Indigenous and nomadic communities across the world have mastered and passed down natural preservation techniques for long journeys. And, historically, the consumption of vegetables themselves, scraps and all, have been linked to diets of slaves and servants in colonial homes – in modern-day Caribbean culture, for example, the heavy appreciation for root vegetables in the cuisine dates back to ancestors having to make do with what they could get. The ready availability, and thus lack of exoticism, of vegetables attached them to the lower socioeconomic classes.

The consumption of, and disgust at, eating the ends of vegetables is thus not separate from both the colonialist and capitalist projects, which together, solidified a class system that was categorised by one’s access to certain goods. Thorstein Veblen’s theory of conspicuous consumption frequently still holds: individuals consume goods and services as a means of displaying power and authority in a public space. We assume, then, that people will try to purchase ‘upwards’ in a bid to move up the class ladder.

We’ve seen gentrification of urban neighbourhoods, appropriation of music and dance, and fetishisation of ancient garments. And in the context of food, we are seeing minority communities being priced out of fresh fruit and vegetables.

The lines of socioeconomic class are certainly not as clear-cut today, but Veblen’s ideas are still prevalent. However, there is also a counterforce, in the form of whitewashed gentrification. Gentrification is literally the opposite of conspicuous consumption: it is the appropriation, fetishisation, and eventual marketisation of minority culture, in such a way that makes it inaccessible to the minorities themselves. We’ve seen gentrification of urban neighbourhoods, appropriation of music and dance, and fetishisation of ancient garments. And in the context of food, we are seeing minority communities being priced out of fresh fruit and vegetables.

It is therefore not just hunger that disproportionately impacts minority communities: it is also nutrition poverty. This is a vital distinction, because while there can always be food on the table, there is a high likelihood that the food might not contain the adequate vitamins and minerals needed to sustain a healthy body; a study published in the Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging found that black women were accessing and therefore consuming fewer vegetables, fruits, nuts and legumes and cereal fibre. Add in the concept of time poverty, with minority communities often flitting between multiple forms of employment and family commitments, and nutritious food is a distant dream.

The issue is not with the ethos behind Zero-Waste movements, but rather with how such movements are playing out in practice

The issue is not with the ethos behind Zero-Waste movements, but rather with how such movements are playing out in practice. The inevitable move to brand the movement, with (usually white) Instagram influencers bringing it to life, is not only shutting communities of colour out of the conversation, but also quite literally out of sustenance. The ‘greenification’ of both staple foods, and food practices themselves, need to be culturally sensitive and inclusive, rather than favouring individual action. But this is another blind spot that will be missed if we continue capitalist pursuits into rethinking food.

Underutilisation is a part of a wider discussion on the circular economy of food, which at present aims to fulfil the dual goal of meeting global demand for nutritious food whilst simultaneously reducing food waste. The Ellen McArthur Foundation’s research into circular food economies in cities – which will be responsible for 80% of food consumption by 2050 – demonstrates the tangible links between food, health, energy and the natural environment. The Foundation’s report offers solutions to these overlapping issues by suggesting that we source food ‘regeneratively,’ that we ‘make the most of food,’ and that we ‘design and market healthier food products.’ Circular economies tout not only environmental recovery, but also social justice, by promising to shorten the supply chains between farmers and retailers. For smallholder farmers in developing countries, the hope is that they will be able to ‘leapfrog directly into circular food systems as they develop.’

It is an ambitious goal, but the omission of rural communities in this ecosystem undermines it.

The Foundation’s report emphasises the need to ‘mobilise unprecedented collaboration between food brands, producers, retailers, city governments, waste managers and other urban food actors’ to make a circular food economy function. It is an ambitious goal, but the omission of rural communities in this ecosystem undermines it. Not only are rural communities often lower down the socioeconomic and income ladders, but in both developed and developing nations, rural communities are intrinsically linked to the agricultural trade and thus fundamental to the food system. The current COVID-19 crisis is highlighting exactly how critical agricultural labour is in maintaining the status quo in a national food supply chain, let alone a global one.

This is green elitism. It is futile to follow environmental science without recognising the tangible impact, both of the climate crisis and of any proposed change, on the communities on the ground. Environmental damage cannot be decoupled from capitalist systems and colonialist, imperialist modes of thinking. Focusing solely on how circular economies work for urban environments in developed nations ignores the fact that resource depletion disproportionately impacts emerging markets, and the fact that these urban environments do not exist separately to the rest of the world: we have one, collective resource pool. In the UK, for example, half of all of our food is imported. If we were to move to a city-centric or island-centric circular food system, would our own farming industry be able to cope with the sudden spike in demand?

In failing to recognise the diversity of urban populations, green movements miss an opportunity to learn from the very minority communities that have been at the forefront of such ‘green’ methods for years

Cities themselves are embroiled in steep income disparities and varying levels of accessibility to public services. Urban-centric climate literature tends to focus on one ‘type’ of urban dweller: the white, male, able-bodied, nine-to-five worker. In failing to recognise the diversity of urban populations, green movements miss an opportunity to learn from the very minority communities that have been at the forefront of such ‘green’ methods for years. As Anke Brons, a PhD Candidate in Environmental Sociology, highlights, communities of colour are not necessarily brought into environmentalism, but rather have been demonstrating ‘green’ behaviours as a means of protecting their physical and financial health for years.

Vegetables – peels, leaves, ends and all – are a staple food for communities of colour and those in lower socioeconomic classes, both as a result of cultural practices and historic classist structures. The green movement risks edging into food gentrification, risking affordability of staple goods by rebranding them to appeal to the conscience of the ‘ethical consumer’. Marginalised groups, particularly those with close relationships of respect to land and food, must be integrated into these movements from the bottom-up, whether zero-waste or circular economy. The struggles of these groups – historical, financial, agricultural, territorial – are a rich encyclopedia of knowledge; they must not be ignored, neither appropriated for ‘green business’. Otherwise, these movements risk working for the few at the expense of the many.

More Reads

Pollution

Silent Spring Revisited: a revolutionary art-science synthesis

Keep readingRachel Carson's images of a 'Silent Spring' bereft of birdsong – robbed by harmful pesticides – are known for launching the Western environmental movement as we know it. In this piece, Rowan Jaines revisits Carson's 1962 classic, arguing that the book's success, and the industry backlash it provoked, can be credited to Carson's powerful synthesis of traditionally artistic and scientific practice – a synthesis that we might still learn from today.

By Rowan JainesKeep readingEcology

Existing in Kinship with Everything

Keep readingThe plant lives of Aotearoa (and the myriad meanings they embody) have long been threatened by Western colonists, facilitated by a belief that an ecosystem’s importance is defined by what it offers humans. Hana Pera Aoake describes a very different Māori worldview – one that emphasises the deep, non-linear interconnections between the people and their plant-relatives, and that continues to resist and flourish in the face of eco-cultural imperialism. Edited by Jackson Howarth.

By Hana Pera AoakeKeep readingPippin’s golden honey pepper, Aunt Lou’s Underground Railroad tomato, the Paul Robeson tomato. Buried in the names of beloved fruits and vegetables is a rich tapestry of Black life, knowledge and history. In this sneak peak into our landmark Issue 10 (which you can pick up here) Amirio Freeman uncovers these stories, exploring how imperial Linnaean naming conventions continue to threaten essential endemic plant names, along with the ways of knowing and remembering that they embody. Illustration by Farida Eltigi.

Keep reading >

History

The Black Histories Hiding in Plant Names

By Amirio Freeman(Article)History

The Black Histories Hiding in Plant Names

Keep readingPippin’s golden honey pepper, Aunt Lou’s Underground Railroad tomato, the Paul Robeson tomato. Buried in the names of beloved fruits and vegetables is a rich tapestry of Black life, knowledge and history. In this sneak peak into our landmark Issue 10 (which you can pick up here) Amirio Freeman uncovers these stories, exploring how imperial Linnaean naming conventions continue to threaten essential endemic plant names, along with the ways of knowing and remembering that they embody. Illustration by Farida Eltigi.

By Amirio FreemanKeep reading- Read more